Got interrupted? Part 2. Tales of two handle tables.

How to give a middle finger to the object manager

Disappointment

After the disappointment from the first post, and after having to redesign the kernel-side of the async system, I decided to give a part 2 for this “got interrupted” series. Which we will be investigating ways to go our way around IRQL limitations in VMEXITs. See the related issue here

How to NOT deal with high IRQL

What I did for HxPosed was simply a global queue which defined which task to execute in which process context. It went well, until it didn’t. That was when I was making the callbacks feature. Which were simply PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineEx wrappers that queue a command to be queued (yeah, I regret that) to be executed.

The order was simple for almost any async function.

- Check if call is async.

- If async, construct the

InsertNameHereAsyncCommandobject. - Box it.

- Acquire global lock queue.

- Queue it.

- Return an

EmptyResponse.

And a worker thread running at PASSIVE_LEVEL IRQL was using KeDelayExecutionThread with 250ms delay. It was messy.

- Wait for 250ms.

- Acquire lock for global async queue.

- Check if there is a new AsyncCommand.

- If no, go to step 1.

- If yes, drop the lock, switch to context of process made the call.

- “Work” the command.

- Switch context to the process made the async call. (Yes! Twice!)

- Probe the shared memory region.

- If writable, write result to the memory region.

- Set the event using

ZwSetEvent.

Do you see the problem here? There are multiple.

- Use after free.

- Heavy reliance on process contexts.

- Poll-based queue. Not event based. Slowwwww.

But what I could do? The async was simply passing a shared memory region and a handle to the event.

No more.

UAF

This was not present until the callback system arrived. Which heavily relies on time outs.

When the user allocates the buffer and sends the request, but cancels it (via dropping the Future), it does not inform hypervisor that the request is cancelled. The memory is freed. Thus, hypervisor writes to it.

But how does ProbeForWrite return Ok then?

Because memory is still writable. That memory was from heap, and even though it was freed, it wasn’t unmapped, it was still in process’s address space. Thus, perfectly valid. Except that it isn’t.

So boom. Heap corruption. We need MDLs.

Refactoring the async system.

So we had to get rid of excessive KeStackAttachProcess calls and a way to stop the UAF.

So I came with this idea: Using MDLs and opening the native kernel event object instead of using Zw* functions.

But how?

Back to the IRQL.

So, we need to open the object itself from handle. Easy thing. We have a function exactly made for that purpose. ObReferenceObjectByHandle. And guess what?

PASSIVE_LEVEL. I don’t understand Microsoft’s desire to page everything. Hell, they even have a function named as MmPageEntireDriver. Just… What is the point? Why hurt the SSD? Just keep things in memory.

Anyway, after ranting enough. I decided to take a deep dive into Windows internals to figure out how to get the object by myself. After all, a handle is just an index in a per process table, right?

The tale of 2 handle tables.

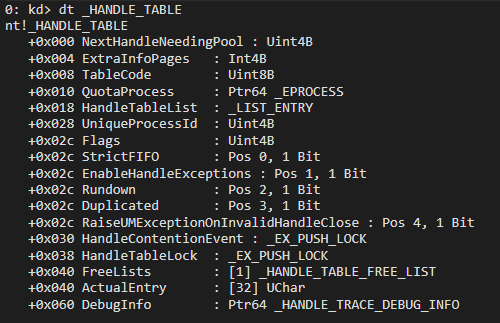

A process’ handle table is stored at ObjectTable field of EPROCESS structure. Which itself is a PHANDLE_TABLE. It’s a complex structure by itself. It grows depending on the demand of handles and has 3 states. Small, medium, large (large can hold up to 2 million handles!).1

So let’s see what that bad boy has to offer for us.

Uh huh. Huh huh. Mhm. Yes. We can work with that.

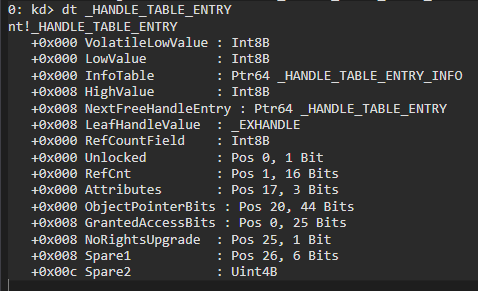

So we have a HandleTableList structure which is supposedly holding a doubly linked list to _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY structures. Which itself is extremely messy.

We can see that it’s not correct given that _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY does not have a ListEntry field or such.

Traversing the handle table manually

To get an inspiration of what to do, let’s take a look at what ObReferenceObjectByHandle is doing.

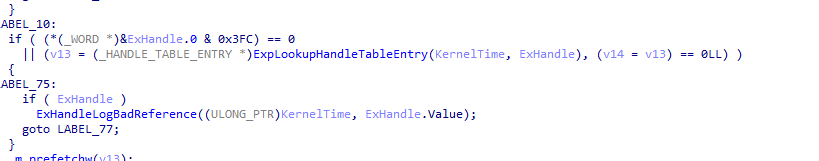

That might be what we are just looking for.

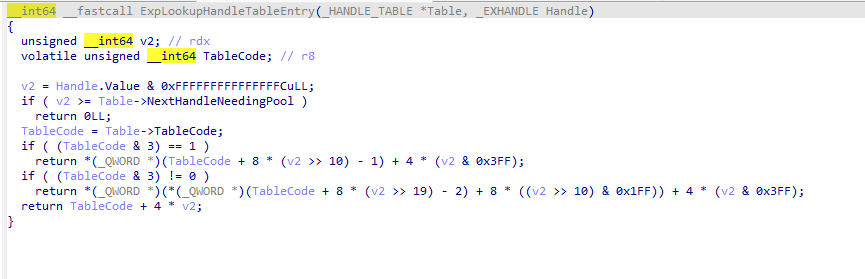

After some digging through WRK, we can extract out its parameters and return value. It

ExpLookupHandleTableEntry takes a pointer to _HANDLE_TABLE and an EXHANDLE. EXHANDLE is just a fancy way of “HANDLE” with some extra flags like kernel or some. It doesn’t bother us. We can use a normal handle value as an EXHANDLE. And it returns an _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY

But wait, that’s not manual!

It’s not. Because traversing handle table manually is pain. Somehow I was never getting the correct entry no matter what I do. I did a lot of research on that, but didn’t turn out to be right. So yeah, we will use ExpLookupHandleTableEntry. It’s safe to assume that this won’t change in future versions of Windows. Since it’s been pretty stable so far. And this saves us from having to get offsets or define _HANDLE_TABLE. Yay!

So how do we get the object?

As we’ve seen from above, _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY has an interesting field named as ObjectPointerBits. It also has a GrantedAccessRights, which was a nice target for a lot of people. But not what our point is. HxPosed gives you kernel access anyway. Who cares about handles?

Ehm. Anyway. As you see from definition, bits 20-44 is what we are looking for. We can quickly whip up a function to read those bits.

There is a caveat tho. This is NOT the full address. We have to add 0xffff’s to beginning of it. So we have to do some math object_pointer << 4 | 0xffff000000000000.

All good, for now.

The ObjectPointerBits field returns the OBJECT_HEADER. Not the object itself. Nice for us, the object body itself is exactly right after the OBJECT_HEADER structure. So if we advance 0x30 bytes from the OBJECT_HEADER, we will get the object!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

let exhandle = _EXHANDLE {

Value: handle

};

let handle_table_entry = unsafe{ExpLookupHandleTableEntry(table, exhandle)};

if handle_table_entry.is_null() {

// invalid handle

return Err(());

}

let object_pointer = unsafe{*(handle_table_entry)}.get_bits(20..64);

let object_header = (object_pointer << 4 | 0xffff000000000000) as *mut u64; // decode bitmask to get real ptr

// object body is always after object header. so we add sizeof(OBJECT_HEADER) which is 0x30 to get object itself

let object_body = unsafe{object_header.byte_offset(0x30)} as *mut T;

References matter

We referenced the object, without actually referencing it. We have the object but we didn’t tell Windows that we are using it. We need to modify the PointerCount field of the OBJECT_HEADER structure. So Windows won’t delete it mid-operation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// TODO: Make this atomic.

pub fn increment_ref_count(object: *mut u64) {

let header = unsafe{object.offset(-0x30)};

unsafe{header.write(*header +1)};

}

pub fn decrement_ref_count(object: *mut u64) {

let header = unsafe{object.offset(-0x30)};

unsafe{header.write(*header -1)};

}

Simple as that.

What about creating handles?

After some more research, I realized that the map itself is in paged pool. But somehow, with this level of IRQL. We are able to access it. I’m not sure how its possible. Probably because its not paged out. But in Windows, it doesn’t matter. You are not allowed to touch paged memory, whether its present or not, on high IRQLs.

So after realizing I can entirely remove async from HxPosed, I went into a problem, “How I will call ObOpenObjectByPointer?”. The answer was same. Research.

Opening ObOpenObjectByPointer, we see an pretty simple function. And a call to ObCreateHandle after some checks.

But ObCreateHandle is extremely huge. We can see there is a lot of security checks happening. We dig through to find a few interesting calls:

ObpIncrementHandleCountExObpInsertOrLocateNamedObject

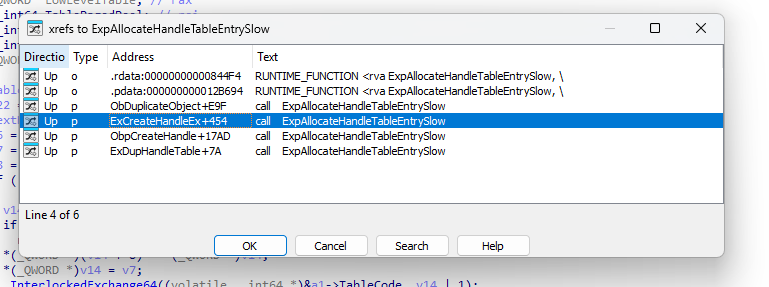

But none of those do us any good. Until we find a call to ExpAllocateHandleTableEntrySlow. This is another function that allocates the actual entry. But it uses paged pool, too. It’s not a problem for us since it somehow works.

So we got a function named as ExCreateHandleEx. Seems like exactly what we are after!

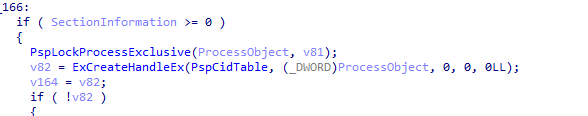

After looking at its xrefs, we see that PspAllocateProcess calls ExCreateHandleEx. With some renaming, we can see how its called and what are its arguments that are our interest.

So first parameter is PHANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY, and second is the object pointer? Great.

So we can form our prototype.

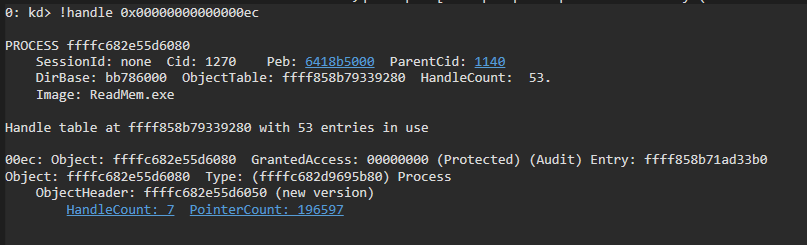

I quickly fired up a driver that calls this function and we will check the handle it created.

1

2

3

4

Irql = KfRaiseIrql(HIGH_LEVEL); // we gotta make sure it works

Process = IoGetCurrentProcess();

ObjectTable = *(PVOID*)((PUINT8)Process + 0x300);

Handle = ExCreateHandle(Process, ObjectHeader);

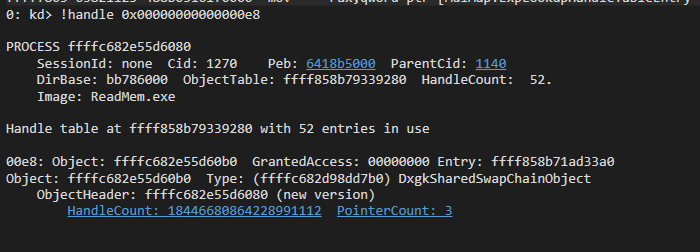

So we got our handle but… Uh?

We can safely say that a DxgkSharedSwapChainObject is not a process object. So what went wrong?

Let’s try with the object header instead of object body.

Yes. That is what we like to see. But there is one problem. The GrantedAccess is 0. The handle is created with 0 access rights. That means we need to access the _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY structure and change those bits we’ve seen earlier.

Bits 0-25 are we need for that. We will just fill it with Fs to get us all access we need. We will use ExpLookupHandleTableEntry to get the entry, again.

1

2

Entry = ExpLookupHandleTableEntry(ObjectTable, Handle);

Entry->s2.GrantedAccessBits = 0x1FFFFFF;

How many times I have to tell….

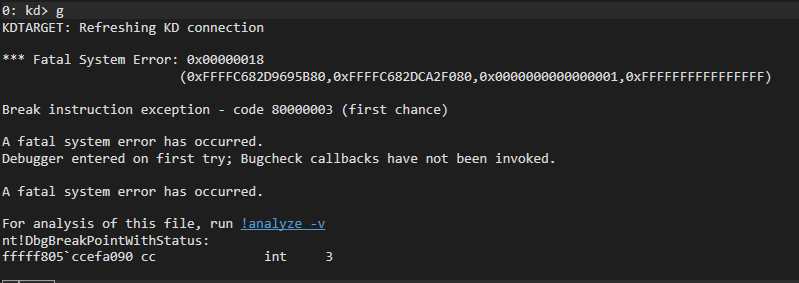

Things are going pretty well, so far. Let’s try to use the handle with TerminateProcess on user-mode and see what happens.

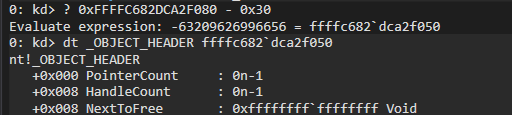

So we got a bugcheck telling us reference count for the object is illegal. Let’s see how that is the case with dt.

That means ExCreateHandle does not increment reference and object count for us. We have to do it ourselves.

1

2

*(ObjectHeader) += 1;

*(ObjectHeader + 1) += 1;

This does the job. There we go. Now we can create and get objects from the handles without help of the object manager. That is amazing!

The Real Deal

Now we can use KeSetEvent to simply set the event. We won’t have to change process contexts now since we have access to the object in system space!

After testing, we see that we easily get a pointer to the object, in a VMEXIT! Yuppy!

I’m not exactly sure if that was the case. I have read this from some obscure PDF. But yeah, probably that’s correct since we have

TableCodefield and its bitmasked usage viaExpLookupHandleTableEntry. ↩︎